Page Summary

- If you are in crisis, call the Upper Room Crisis Hotline at 1-888-808-8724. Don’t suffer in silence! You are loved and we want you to live!

- The evidence does not support the effectiveness of either social transition or medical pathways in reducing suicides or suicidality among people experiencing gender discordance.

- There is some evidence to suggest that increased suicidality is caused by accompanying psychiatric comorbidities and ACEs that might manifest earlier than gender discordance, as is the case with parental mental illness.

Does someone’s internal sense of their gender determine their existence as male, female, or other?

Medical objections to the previous article, part 2

Listen to this article

Content warning: sensitive issues, including suicide.

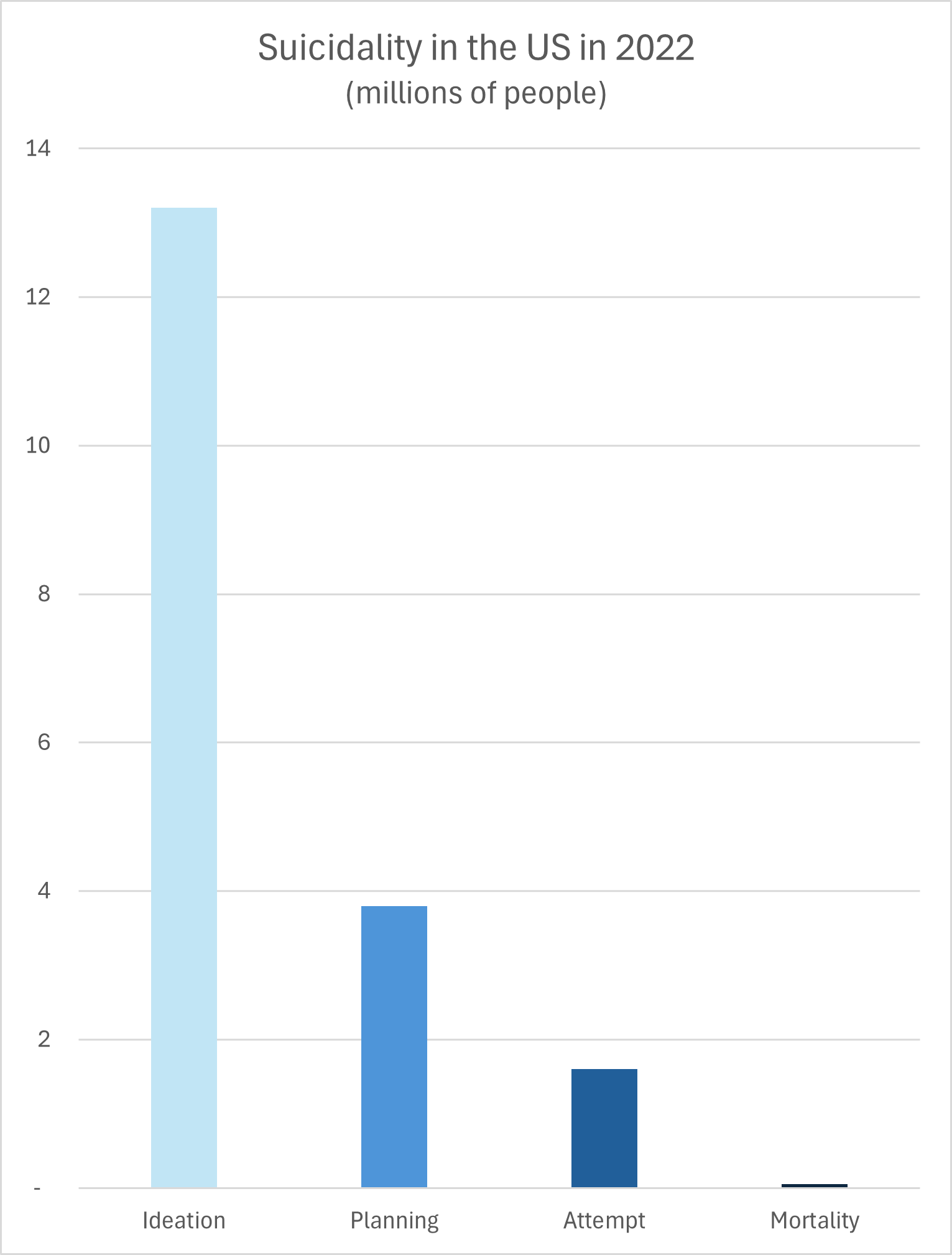

General suicidality out of a total population of 332 million

First three categories only included adult populations

Data from CDC Suicide Data and Statistics

If we don’t provide GAC for transgender and non-binary young people, won’t they continue to have poor mental health outcomes, including suicide, at a much higher rate than the general population?

Before we address the question, if you are in crisis, call the Upper Room Crisis Hotline at 1-888-808-8724. Don’t suffer in silence! You are loved and we want you to live!

Some prominent media outlets and advocacy groups tend to fuel this narrative with misleading reporting that often violates the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention’s guidelines for reporting about the subject in a safe and accurate manner. The British government’s leading advisor on suicide prevention has also urged against using these alarmist claims, warning that they are potentially harmful and not supported by reliable evidence.

A more detailed discussion of the question follows below, but there was an overall conclusion reached by the Cass Review as a result of its systematic reviews of the existing evidence. The Cass Review concluded that the evidence does not support the effectiveness of either social transition or medical pathways in reducing suicides or suicidality.1 An example of the sort of study included would be a 2021 study from California examining major psychiatric encounters, including suicide attempts, before and after surgery.2 That study showed there was approximately equal or greater risk after surgery than before. This is a serious problem, but GAC isn’t the way to solve it.

“Suicidality” is a broader category than death by suicide. The term includes several stages: seriously thinking about committing suicide (also known as “ideation”), making a plan, making an attempt, and actually dying by suicide.

Suicidality is sadly more common among young people who experience gender discordance than among the general population, though the exact statistics in the United States are difficult to establish. Family conflict, bullying, and abuse increase the risk of suicidality for these already-vulnerable people, and should not be tolerated.

This risk, while elevated, is still low. A study of the largest pediatric gender clinic in the world, located in London, found that out of about 15,000 patients, four actually died by suicide, or 0.03%. Those four were evenly divided between those who had an appointment at the clinic and those who were on the waiting list for an appointment.3

A common narrative goes significantly further. Advocates claim that negative mental health outcomes like these can be avoided by making GAC available to people with gender discordance. The narrative was especially fueled by a 2019 study by Richard Bränström and John Pachankis that appeared to show a causal link between GAC and reduced need for mental health treatment. At the time, the study made the news, but the following year the journal that published the study issued a retraction. A review of the data found problems in the study’s design, meaning that “the conclusion… was too strong.”4 This retraction did not make the news like the original study. The picture is more complicated than popular media narratives lead audiences to believe.

A commonly overlooked part of the picture is the presence of accompanying risk factors. Psychiatric “comorbidities” (such as clinical depression or anxiety) and Adverse Childhood Experiences or “ACEs” (such as the loss of a loved one or abuse) are disproportionately present in people who experience gender discordance.5

A 2024 study from Finland spanning over 20 years showed that the difference in suicide rate almost disappeared when the cohorts were controlled for psychiatric comorbidities.6 Even then, the variable couldn’t be completely accounted for, since those who were approved to receive GAC “presented less commonly with needs for specialist-level psychiatric treatment”.7 In other words, people who received GAC were already less of a suicide risk to begin with, compared with others experiencing gender discordance who were not approved because of some disqualifying factor. In that case, there would be no evidence that GAC helped them avoid suicide, if they weren’t at elevated risk in the first place.

Advocates tend to dismiss their significance, arguing that these risk factors result from external reactions to an individual’s gender discordance. The causal chain is thought to work like this:

Step 1: An individual (Rob) presents signs of “being transgender”.

Step 2: Because of this, Rob suffers direct mistreatment at the hands of family or bullies and suffers indirect marginalization from wider society.

Step 3: Because of these ACEs, Rob develops comorbidities and his mental health declines.

Step 4: Rob develops suicidal tendencies.

This narrative assumes that comorbidities and ACEs are more common because they occur after the first signs of gender discordance. The question is whether or not the comorbidities and ACEs tend to occur as an effect of someone manifesting signs of gender discordance.

Does the available research support this causal narrative?

There isn’t much research available about the timing and causality between gender discordance, comorbidities, ACEs, and suicidality. The research that is available suggests a lack of connection, that the comorbidities and ACEs could still have occurred without the presence or indication of gender discordance. This is especially the case when looking not at the patients’ comorbidities only, but their parents’ as well.

Parental mental illness is much more likely to begin before their children manifest gender discordance or are even born. A 2021 study from Australia found that over 52% of patients with gender discordance had a mother with mental illness and 40% of patients had a father with mental illness.8 The study didn’t indicate how many of those patients had both parents with mental illness or only one. Another 2021 study from Australia found that over 63% of patients with gender discordance had at least one parent with mental illness.9

There are a host of other conditions and risk factors mentioned in the study, some of which are more likely to occur before gender discordance than others. The causal narrative advanced by advocates of GAC just doesn’t have clear support in the available research, because the picture is much more complicated.

1) Cass H., et al. (2024). Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People: Final Report, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 31-33. https://adc.bmj.com/pages/gender-identity-service-series

2) Dallas, K., Kuhlman, P., Eilber, K., Scott, V., Anger, J., & Reyblat, P. (2021). Rates of Psychiatric Emergencies Before and After Gender Affirming Surgery. Journal of Urology, 206 (Supplement 3), e74–e75. https://doi.org/10.1097/JU.0000000000001971.20

3) Biggs M. (2022). Suicide by Clinic-Referred Transgender Adolescents in the United Kingdom. Archives of sexual behavior, 51(2), 685–690. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02287-7

4) Kalin, N. H. (2020). Reassessing Mental Health Treatment Utilization Reduction in Transgender Individuals After Gender-Affirming Surgeries: A Comment by the Editor on the Process. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(8), 764–764. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060803

5) Kozlowska K., et al. (2021). Attachment Patterns in Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.582688

6) Ruuska S, Tuisku K, Holttinen T, et al. (2024). All-cause and suicide mortalities among adolescents and young adults who contacted specialised gender identity services in Finland in 1996–2019: a register study. BMJ Mental Health , 4(27), e300940. https://mentalhealth.bmj.com/content/27/1/e300940

7) Kaltiala, R., Holttinen, T., & Tuisku, K. (2023). Have the psychiatric needs of people seeking gender reassignment changed as their numbers increase? A register study in Finland. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists, 66(1), e93. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10755572/

8) Kozlowska, et al, 9.

9) Kozlowska K., et al. (2021). Australian children and adolescents with gender dysphoria: Clinical presentations and challenges experienced by a multidisciplinary team and gender service. Human Systems, 1(1), 70-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/26344041211010777